The Great Molasses Flood of 1919, Boston's version of Pompeii, surely ranks as one of the city's worst disasters - and it's hard to think of a ghastlier one.

On January 15th, the outdoor temperature rose to an unusually (for Boston in January) balmy 45° F.

Shortly after noon in Boston's North End, a rusty, already-leaking tank containing 2.3 million gallons of fermenting, smelly, sticky molasses at the bottom of Copp's Hill exploded.

Metal rivets 1/2 inch thick were torn apart and flew through air like shrapnel. Some of them cut the steel girders of an elevated railway.

The force of the explosion caused some buildings to collapse and knocked others off their foundations.

The explosion also created a vacuum immediately after the initial blast, which destroyed even more buildings, dragged a truck across a street, and pulled a train off the tracks.

And then the flood of molasses began.

The explosion sent what an eyewitness called a “30 foot wall of goo” (later determined to have been about 40 feet) down Commercial Street at a speed estimated to be 35 mph.

As the gooey mess covered the neighborhood and spread out in a 2-to-3 foot thick layer across downtown, it buried and drowned people and animals in its path.

Top Photo: Destruction in Boston's North End under the elevated tracks after a tidal wave of molasses swept down the street - Photo credit: Public domain

Why Was Molasses in that Tank?

In case you're wondering exactly what molasses is, it's the residue that's left over after sugar cane is boiled to extract sugar. It has some nutritional value and is used to produce products such as cattle feed and rum - and of course it's a key cooking ingredient for things like gingerbread, ginger cookies, Boston brown bread, and Boston baked beans. In World War I, it had also been used in making some munitions.

Why did Boston store so much molasses in a tank?

Boston had long been a major molasses center and was a major player in the "triangular" trade dealing in molasses, rum, and slaves.

Plantations on the English colonies of Jamaica and Barbados grew sugar, processed it into molasses, and shipped it to Boston where local distillers turned it into rum. New England ships carried the rum to Africa, and traded rum for slaves.

The ships then carried the slaves to the islands, sold them to work on the plantations, and then returned to Boston filled with more molasses. Ship owners, plantation owners, and distillers made fortunes by trafficking people, sugar, and rum.

Even after the slave trade finally ended, Boston continued to produce vast quantities of rum. As a result, the distillers needed lots of molasses.

The tank that exploded in 1919 was the city's largest. Ironically, the molasses in this particular tank was to be used for distilled alcohol, not rum ... although that detail didn't matter to those who died.

The tank's owner, United States Industrial Alcohol, had been warned that the tank was leaking.

Their response?

They painted the tank brown to camouflage the dripping molasses.

Within hours after the explosion, their lawyers exploited the anti-Italian sentiments already running high in Boston by blaming the explosion on Italian anarchists.

Death Toll from the Great Molasses Flood

A total of 21 men, women, and children, 12 horses, and uncounted numbers of dogs and cats died in the Great Molasses Flood. The disaster injured at least another 150 people.

Rescuers—police officers, firemen, Red Cross volunteers, good Samaritans—quickly became stuck in it and had to be pulled out themselves.

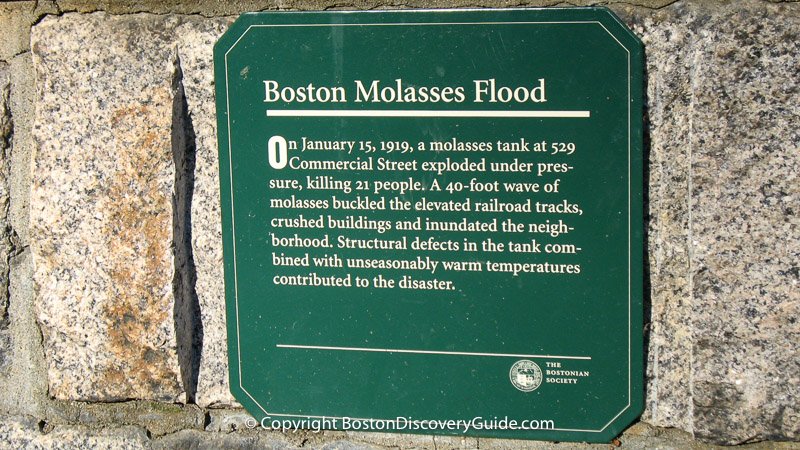

Today, only a small plaque in the North End’s Puopolo Park commemorates the disaster—although some local residents claim that even now, on a hot summer day, you can still smell the molasses.

How to Visit the Site of the Great Molasses Flood

The best way to see the site where the disaster began, marked by the plaque in in Puopolo Park, is to make a small detour while walking along the self-guided Freedom Trail tour in Boston's North End.

The plaque is right behind Copp's Burying Ground, one of the North End Freedom Trail sites.

When you're walking along the Freedom Trail in the North End and reach Commercial Street, instead of turning right onto Hull Street to go up to Copp's Hill, just continue east on Commercial Street for a few hundred yards. You'll see the park on your left, near the water.

The sign is next to the sidewalk, on a low wall - you'll have to kneel down if you want to photograph it straight-on. It's easy to miss - after all, this disaster is not exactly a source of civic pride.

More Ways to Experience Boston History

Boston Insider Tips: Visiting the Great Molasses Flood Site

- Address of plaque: Puopolo Park, 529 Commercial Street, North End, Boston

- Closest T station: Green and Orange Lines/North Station

- Where to look: Next to the sidewalk, near the children's playground and bocce court

- Hours: None (it's by the side of the street)

- Visiting with children: They'll enjoy playing in the Puopolo Park playground while you watch the nearby bocce players who almost always have a game going. If you're visiting in cold weather, the public ice hockey rink to the left of the park often has hot chocolate and coffee for sale (or you can even ice skate there)- plus you're just a few blocks away from the North End's super bakeries/coffee shops along Hanover Street.

- More to see nearby: Walk up to Copp's Burying Ground on the Freedom Trail - the easiest way to get there is to go back up Commercial Street and then turn left onto Hull Street (look for the Trail's red stripe). It's about a 2-minute walk.

- More information about the Flood: Dark Tide: The Great Boston Molasses Flood of 1919

by Stephen Puleo

Where to Stay in Boston's North End

https://www.booking.com/hotel/us/bricco-suites.en-us.html?aid=364168More Articles about Boston History

- Boston's Freedom Trail - Walk along Boston's path through history

- Books about Boston - The best books about Boston to read before and after your visit

- Boston Sightseeing Tours - See the best of Boston

- Boston's North End - Find out what to explore and where to eat